Chapter Two: Organizing Escape Networks

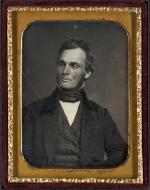

To understand how the Underground Railroad worked, consider the example of Sam Nixon, also known as Dr. Thomas Bayne (c. 1821-1888). Sam Nixon was an enslaved African American owned by a dentist in Norfolk, Virginia. He not only kept accounts for his master's practice, but also became a skilled dentist himself. Soon, he was asked to make house calls to white families around the port community.

Because of these house calls, Sam Nixon had greater freedom of movement than most other slaves. His special position and extensive nighttime travels allowed Nixon to serve as an especially effective agent for the Underground Railroad. He helped slaves in Norfolk find steamship captains who were willing, for a price, to transport them to Philadelphia.

After receiving an anonymous letter from Philadelphia warning that his activities might have been exposed, Nixon made his own escape aboard a friendly ship in early 1855. Because of difficulties along the voyage, he was dropped off in New Jersey instead of Philadelphia. He went to the home of a Quaker woman named Abigail Goodwin, who was in regular contact with the Philadelphia committee that organized the region's Underground Railroad.

Goodwin wrote William Still, the group's principal coordinator, that some of the other agents in New Jersey thought Nixon was "an imposter," and a "great brag." No one, she wrote, could believe that he was truly an accomplished dentist. When he arrived in Philadelphia, he was interviewed to verify his story. Satisfied that he was not an imposter, the Philadelphia committee then sent Nixon on to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

As a free man, Nixon changed his name to Thomas Bayne and opened his own dentist's office. The Philadelphia committee continued to monitor his progress, sending medical books and other materials when he needed them. Dr. Bayne became prominent in his adopted community and was even elected to the town council in 1860. After the Civil War, he returned to Norfolk and became a leader in the Republican Party, almost winning a seat in Congress.

Of course, not every escaped slave became as prominent as Sam Nixon, but many runaway slaves who passed through Philadelphia shared aspects of his experience. Fugitives arrived in Pennsylvania not just by crossing the Mason-Dixon Line, but also by sea routes. Successful escapes almost always required money – to pay ship captains or purchase food – so many runaways came from the elite pool of skilled workers who were allowed to hire out some of their labor. Once in Philadelphia, escaping slaves found a surprisingly efficient network in place to help them relocate and adjust to free life. Many headed for Canada, but a significant number dispersed across the free northern states.

Mason-Dixon Line, but also by sea routes. Successful escapes almost always required money – to pay ship captains or purchase food – so many runaways came from the elite pool of skilled workers who were allowed to hire out some of their labor. Once in Philadelphia, escaping slaves found a surprisingly efficient network in place to help them relocate and adjust to free life. Many headed for Canada, but a significant number dispersed across the free northern states.

In Philadelphia, runaway slaves encountered a local Underground Railroad operation that described itself as the "vigilance" movement. The Philadelphia Vigilance Committee was founded in August 1837 and conducted its early meetings at the African Zoar Methodist Church. Within two years, the movement was reorganized under the leadership of

African Zoar Methodist Church. Within two years, the movement was reorganized under the leadership of  Robert Purvis, a remarkable figure who dramatically increased the scope of the group's efforts. During the early 1840s, the Vigilance Committee handled about 100 fugitive cases per year. They kept records of their assistance and even held receptions, or what they called "soirees," to help raise funds. Ultimately, however, their aggressiveness made them targets and the organization suffered a series of financial and political setbacks. Leadership positions changed frequently. By the end of the 1840s, there was practically no organized system left in Philadelphia or anywhere in Pennsylvania.

Robert Purvis, a remarkable figure who dramatically increased the scope of the group's efforts. During the early 1840s, the Vigilance Committee handled about 100 fugitive cases per year. They kept records of their assistance and even held receptions, or what they called "soirees," to help raise funds. Ultimately, however, their aggressiveness made them targets and the organization suffered a series of financial and political setbacks. Leadership positions changed frequently. By the end of the 1840s, there was practically no organized system left in Philadelphia or anywhere in Pennsylvania.

Then came a sectional deal between the free and slave states, called the Compromise of 1850. Part of this compromise offered the South a tougher federal fugitive slave law in exchange for the admission of California as a free state. These new rules made it easier to pursue fugitive slaves in northern states. Pennsylvania's abolitionists were outraged, and fears were sparked among free blacks of kidnapping raids targeting their youth. For many, it was like a declaration of war.

Across the state, antislavery groups reorganized. Aggressive new committees in places like Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Lancaster County came together out of desperation and anger. The movement was most active in Philadelphia. There the new Vigilance Committee turned over its Underground Railroad activities to William Still, the hardworking clerk in the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society office. Under Still's leadership, the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee became the hub in a far-flung network that extended up and down the Atlantic and across the state of Pennsylvania.

William Still, the hardworking clerk in the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society office. Under Still's leadership, the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee became the hub in a far-flung network that extended up and down the Atlantic and across the state of Pennsylvania.

Still corresponded regularly with agents in places like Harrisburg, Lancaster, Norristown, and York. He worked closely with wealthy black businessmen like Stephen Smith and

Stephen Smith and  William Whipper, who operated a lumberyard near the Susquehanna River. Smith and Whipper teamsters often brought fugitives along with firewood on deliveries to Philadelphia.

William Whipper, who operated a lumberyard near the Susquehanna River. Smith and Whipper teamsters often brought fugitives along with firewood on deliveries to Philadelphia.

He supported the efforts of brave figures like Thomas Garrett, a Quaker from Delaware, who often relayed "passengers" on the Underground Railroad from legendary "conductor" Harriet Tubman. In Philadelphia, he directed runaways to various safe houses, like his own residence or the

Thomas Garrett, a Quaker from Delaware, who often relayed "passengers" on the Underground Railroad from legendary "conductor" Harriet Tubman. In Philadelphia, he directed runaways to various safe houses, like his own residence or the  Johnson House in Germantown.

Johnson House in Germantown.

The Underground Railroad was never as organized as its name implied, but by the 1850s there was a regular network of agents in Pennsylvania. These agents worked together to help care for, transport and relocate fugitives once they arrived within the state's borders.

Because of these house calls, Sam Nixon had greater freedom of movement than most other slaves. His special position and extensive nighttime travels allowed Nixon to serve as an especially effective agent for the Underground Railroad. He helped slaves in Norfolk find steamship captains who were willing, for a price, to transport them to Philadelphia.

After receiving an anonymous letter from Philadelphia warning that his activities might have been exposed, Nixon made his own escape aboard a friendly ship in early 1855. Because of difficulties along the voyage, he was dropped off in New Jersey instead of Philadelphia. He went to the home of a Quaker woman named Abigail Goodwin, who was in regular contact with the Philadelphia committee that organized the region's Underground Railroad.

Goodwin wrote William Still, the group's principal coordinator, that some of the other agents in New Jersey thought Nixon was "an imposter," and a "great brag." No one, she wrote, could believe that he was truly an accomplished dentist. When he arrived in Philadelphia, he was interviewed to verify his story. Satisfied that he was not an imposter, the Philadelphia committee then sent Nixon on to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

As a free man, Nixon changed his name to Thomas Bayne and opened his own dentist's office. The Philadelphia committee continued to monitor his progress, sending medical books and other materials when he needed them. Dr. Bayne became prominent in his adopted community and was even elected to the town council in 1860. After the Civil War, he returned to Norfolk and became a leader in the Republican Party, almost winning a seat in Congress.

Of course, not every escaped slave became as prominent as Sam Nixon, but many runaway slaves who passed through Philadelphia shared aspects of his experience. Fugitives arrived in Pennsylvania not just by crossing the

In Philadelphia, runaway slaves encountered a local Underground Railroad operation that described itself as the "vigilance" movement. The Philadelphia Vigilance Committee was founded in August 1837 and conducted its early meetings at the

Then came a sectional deal between the free and slave states, called the Compromise of 1850. Part of this compromise offered the South a tougher federal fugitive slave law in exchange for the admission of California as a free state. These new rules made it easier to pursue fugitive slaves in northern states. Pennsylvania's abolitionists were outraged, and fears were sparked among free blacks of kidnapping raids targeting their youth. For many, it was like a declaration of war.

Across the state, antislavery groups reorganized. Aggressive new committees in places like Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Lancaster County came together out of desperation and anger. The movement was most active in Philadelphia. There the new Vigilance Committee turned over its Underground Railroad activities to

Still corresponded regularly with agents in places like Harrisburg, Lancaster, Norristown, and York. He worked closely with wealthy black businessmen like

He supported the efforts of brave figures like

The Underground Railroad was never as organized as its name implied, but by the 1850s there was a regular network of agents in Pennsylvania. These agents worked together to help care for, transport and relocate fugitives once they arrived within the state's borders.